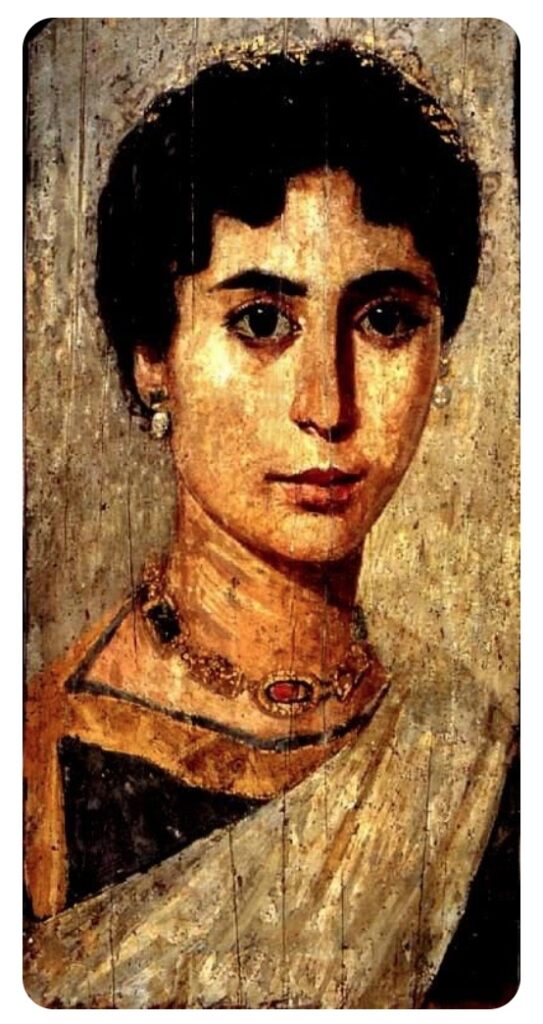

HYPATIA (b. 350–370 — d. March 415 A.D.) was a Neoplatonist philosopher and scientist, and a leading academic and teacher in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt. Her students came from all over the known world, from both inside and outside the Roman Empire. She admitted both Christians and pagans to her classes — she apparently observed no distinction between the two — as well as both men and women. Alexandria was one of the main centres of early Christianity, while still having a large and active pagan community. Hypatia became involved in a political dispute between Cyril, the Christian Patriach of the city, and Orestes, the Roman Prefect, who was a pagan.

Her death was ordered by Cyril (who is now Saint Cyril, a Catholic ‘Church Father’), in 415 A.D. A Christian mob attacked her outside her house, and dragged her to a church. There, they flayed her with seashells and pottery shards, then dragged her through the streets, before dismembering and burning her. At which stage of this torture she died will never be known, but one account describes her ‘convulsing limbs being torn from her flayed body’.

Air for Fire

Those who had survived the flood by taking to the mountains or the tops of the highest hills returned to the valleys and plains, and there they found that everything was covered with silt and mud and debris, and they sighed and set to work.

And even though the heat of the sun would sometimes dry the land until it cracked, and other times the rain would come so heavily that the crops were washed away, life went on. Somewhere, animals and seed had survived and what was needed for building was found, and so, although life was harder than it had been before the change, and it was uncertain, it did go on.

But that was all a very long time ago. Things settled down. Today, we have order.

*

“Cardinal Synesius,” — I have been asked more than once, in so many words — “you were close to the pagan Hypatia, one of her students — what really happened? And how is it that you have become a Cardinal?”

Very well, I shall break my silence. Here is what happened concerning the pagan Hypatia.

*

“Librarian…”

I am watching the approaching Walkers from the main window of the Soil Feeder Archive. They clank, wheezing steam and smoke, through the corn fields; the foliage thrust aside by their iron flanks, rows crushed beneath their riveted hooves, their crews unaware or uncaring of the damage they are doing to the crops.

I hear her sigh. She has come to stand beside me. “What do they want now? Are we expecting anything?” She says it to herself; there is no use asking me.

Librarian Hypatia is… well, one of them. Half born, half made. She is a relic of the old world; we don’t grow them like her any more, and we certainly don’t make them like her any more — not that we could; even if we wanted to. We don’t stand as straight or tall, we don’t think as fast, and we don’t remake ourselves the way they are built to. They are from the past, a past not like anything you or I have ever known. Most people these days don’t talk about the ones like her. Me? Oh, I want to know…

Hypatia has been the Head Librarian at the Serapeum since her predecessor became something to do with the Cardinals (apparently an offer he could not refuse). He taught her well; she knows where every Soil Conditioner, every Enhancer, every Charm and Relic, every Amulet, every Air, Karma and Water Filter and every book and scroll is kept. I think that the entire contents of the Serapeum Library are catalogued in her mind. And I get the feeling that she understands it all, as well.

When the Walkers bring in shipments from the Cardinals’ factories, she knows where each box and crate should go, and when the time comes to send stock out to the markets, she knows what is needed and where. Without her, the markets would barely work. There would be chaos.

And of course I love her, beyond all reason; but I have never told her that, and that is something I regret, because now I never will. So please, say nothing, to anyone.

*

The Walkers are Machinist Tippit’s. We know him.

“New stock,” he says, taking a glass tube of documents from a pouch in his suit and handing it to me. He won’t hand it to Hypatia; he never does.

We have never seen Machinist Tippit’s face. We have never seen what hides behind the stitched leather mask, or the obsidian darkness of the eyeshieldings; even his gait seems hidden beneath the recesses and tubing of the hermetically sealed suit he wears.

I open the tube.

“Fire Feeders,” he says, before I have a chance to begin reading. “There have been new developments with fire.” His voice has taken on a new tone; hubris, I think it is called. I do not like it.

Workers, strapped into clanking and hissing lifters, are already unloading crates of the new devices from the Walkers’ dark holds.

“All instances of fire will now require one of these. All instances…” — he pauses briefly — “New developments with fire,” he repeats pointlessly.

Hypatia reaches into a crate and retrieves a cylinder of tinted glass, apparently empty, and mounted in a framework of brass piping and tubes, from which extends an array of knobs, keys, and valves.

There is no sound as she moves, her tattooed skin slides easily among the prosthetics. Her machinery moves with practiced, easy precision. Her eyepiece clicks almost imperceptibly as she studies the device.

“Machinist Tippit, on whose authori…?”

“The Council of Cardinals,” he interrupts her. The Machinist hides neither his impatience nor his disdain. He does not like the Serapeum, and he does not like us. “Every instance of fire, whether industrial or domestic, must be fed the output from Valves Two, Four, and Subletting Valve D, which must be engaged concomitantly with the Release Control Activator and the Filter Engagement at Locus Two. We…” — he gestures with a gloved hand, in such a way that it is clear that he is referring to himself in particular — “…will be adding Fire Infringements to the list of Surveillable Activities and Warrantable Exigencies. In short, Librarian, every fire will require a Fire Feeder.” He pauses, for a rasping breath. “And your… establishment, of course, will distribute them.”

“I see. New developments with fire, indeed.” Hypatia hands the device to him, smiles as he hesitates before reaching to take it. Even through his mask and suit, his discomfort at the thought of physical contact with her is palpable. “No doubt this has all been well thought out. Good day, Machinist.” She turns to me. “Come, Synesius.”

As she turns to leave, Hypatia gives me the look that I have seen before; the one that means — there is more to say, and — but not here and — oh, who are these clowns? and — be careful … all somehow rolled into one.

You might think that she could be staid, or too studious (do they mean the same thing? I would have to ask her, that’s the sort of thing she knows without having to open a book or a scroll), or perhaps she might be quiet, or even dour. She is a Head Librarian, after all, so none of these would be a surprise, would they?

But none of this is the case. She has a raw, untrammelled,this-is-what-it-is intelligence. Like a zebra, she cannot be tamed. She applies her mind to whatever she chooses, with an enthusiasm that, I know, some see as wanton. She disturbs some people, makes them uneasy.

She does this: she traces and records the paths that the birds draw in the sky and the creening of the fish in the streams at night, and the height of the Silverkros flower stalks after three days of rain, and the rhythm of cloven hooves, which when enumerated, makes her heart thrill — and she says that there are so many ideas and facts, and things that might just be facts, that sometimes she feels as though her mind is going to explode in a wonderful kaleidoscope of thoughts, and each thought is a flame, or a spark, and it’s like a huge, endless orgasm of stars, and thinking, and wonder, and gratitude, and love for it all, and amazement that it can be so deep and clear, and full of light, and steal your breath without trying at all, or really doing anything, and she laughs and says that’s what thinking is, and that’s what science is, and what love is, and it’s all one thing; and there’s no difference between any of it.

So. I can’t argue, can I? I just say yes.

*

“I do not trust the Machinists, Synesius.”

I know. I say nothing. Pathetically, I hope that my silence will encourage hers. Things are complicated enough already; but she continues.

“And I do not like these Fire Feeder things. There is something wrong.”

Of that, I am not so sure. Their reasons may be obscure at times, but the rule of the Cardinals gives us order. They keep us all fed, they keep the Markets full. They have allowed the Library to exist; the Theological Office pays many of our expenses. And the people have their Amulets and their Soil Conditioners and their Filters — all at the behest of the Cardinals. So yes, I am unsure.

“I am going to look into this.” Hypatia’s eyes ripple with anticipation. She writes a note on her arm, on the square of bare skin — often used for this purpose — just beside the hasp of her left elbow assembly. When she writes there, it is always something that she will get to very soon.

I finally accept that I must say something.

“I will be busy, cataloguing the soil samples from the farms,” I say. “Perhaps I will help you later,” I add, intending, but failing, to lie.

*

I go to the Market sometimes, when I need time and space to think. I know there’s some sort of paradox there. The Market is crowded, full of noise and chaos. Despite being at the foot of the cliff face that the Library dominates, and therefore close enough for the two to be considered parts of a whole, it always feels like a world apart.

Everything in the Library feels so important, but in the Market there are so many things to do without, and it all feels so unimportant. Oh… it’s not worth getting complicated about… I come here to think, that’s all.

They have been selling the Fire Feeders here for a month now. A stern-faced Fiscal Probity Marshall from the District Planning College has given the stallholders who qualify the requisite paperwork and certificates; she has collected the Onsellers’ Fees and License Application Bonds, and has seen that the Market Committee’s Undertaking to Accept Responsibilities Charter has been amended, cited, ratified (twice), and signed.

Pending approval by the Inspectors from the Planning College and countersigning by the Theological Office, everything is in order. The stallholders will soon be able to make formal applications for permanent licenses.

As always, Croesus the Lydian is there, with his piles of Magnesium Amulets (for the pig farmers) and Fertility Harmonic Essentials (for the croppers, and for domestic use); and his collection of Conditioners and Filters, of course. Since the Planning College ended the sale of real food at the Markets, traders like Croesus have done well.

Masked though he is, I recognise him by his modifications. He wears the crudely articulated but well-sealed suit of a Trader, not all that different from the suits worn by Farmers and Labourers. The corrugated leather outer skin and pneumatic tubing protects him from the air, and the heaviest eyeshieldings available protect his sight from constant exposure to the glare of the sun. All going well, he will not be blind for some years yet.

“Synesius! Look at this…” Croesus holds up one of the new Feeders.

“Yes, I know. I’ve seen them.”

Croesus grunts. “These things… look what they’re telling us…”

He hands me a sheet. Yes, I’ve seen this before, as well. But I stand there, and I read it again. The Cardinals have taken scientific advice to the effect that raw fire is destructive to the air; that for the sake of the common good, and so that the air is not consumed and so that all life on the earth does not perish, if not very soon then at least soon, and if not soon then within a few short generations, and do you not care about your children, and what sort of world are we going to leave for future generations?… and so on, and so on, then on account of all those things, and for the common good, the Council of Cardinals has decreed that all fire must be accompanied by a Fire Feeder, and that any case of fire being unattended by a Fire Feeder is most deleterious in its effect on the common good, and will be dealt with appropriately — which is to say, harshly.

All this said, the sheet finishes with the admonition that the Machinists will police the new regulations vigorously.

I had forgotten about all this. Or I had tried. Hypatia has seemed preoccupied for the last week, and I know it has to with these accursed cylinders. Her work has suffered, and her mood has changed. The notes that she has been writing on her clothes and skin have been taking on a different tone, one that I haven’t seen before, and on several occasions, she has even hidden them from my sight.

I sigh. I know Croesus, I know that he will have something more for me. “Alright, my friend. Tell me…”

It is easier for him to take me to his village.

*

“This,” he says, as he shows me an iron smelter with furnaces that are cold and silent. “They cannot afford the fees, nor the Scribe to complete the forms.”

“And this,” as he opens the door of a farmer’s hut, and someone hurries to hide an illegal flame. “They do not qualify.”

“And here.” A seed winnower has left a week’s work behind, to go to prison because of unpaid debt. His yard is in disarray. “His family will wait for a time, and then they will despair, and then they will go, and the last of the seed will disappear into the wind.”

“Tell him, Croesus,” the villagers say, when they see the insignia of the Library on my suit. “Show him the ruined food, the empty purses, animals and children gone hungry for fear of the Walkers who come stalking fearsomely out of the mist, how we struggle to share one Fire Feeder between too many hearths… We were poor before, and now look at us… At least we have our faith, and our amulets…”

I have seen enough. “These things are the ruin of these people,” I say.

“You have it, my friend,” Croesus replies. “There was a time when I would happily have made money by selling toys and trinkets to these people, but no more, Synesius. I have done this for long enough.”

*

When I return, Hypatia is in her laboratory. Something I almost recognise is being dismantled, sprawled across a table, a collapsed cage of tubes, clockwork, and instruments.

“Librarian. I will help you.”

She barely looks up, but I do see a smile. “At last. Now, take this. And this. Dismantle them. See whether they match. Whether they can serve a common purpose, or whether they are specific to the tasks which they apparently perform. And then put them back together. Please.”

And soon I know what she has been doing, and that she has been right all along.

*

She has explained everything. It is among her best work, I am sure. The rest of us post copies of it on doors and walls in the villages, hand them out at the Market below the Serapeum and at all the other markets — as far as we can reach.

Soon everyone knows what she has discovered; that the Fire Feeders do nothing. They are useless, inert, their parts are not internally connected in any way that serves a function. Everything about them and of them and in them is for show, and does precisely nothing.

Hypatia presents her findings in words and pictures and supports her case using anecdotes, comparisons, metaphors and similes. The point can escape no one; the argument is undeniable. The word spreads through the markets, and beyond, to the villages and farms, to the other libraries, to the large cities… Soon, the news has travelled everywhere, and soon after that, no one is buying Fire Feeders any more.

Crowds gather and burn their Certificates and Permissions and Notices of Allocation on fires lit, pointedly and loudly, without the aid of Fire Feeders. Feeders are broken and trampled and thrown at the officers from the Planning College, and then at their Walkers as they retreat, shamed, unratified, and penniless.

The priests from the Theological Office watch, conferring in low, troubled voices.

I am concerned. “This could get out of control,” I say to Hypatia.

She smiles. “A free mind cannot be commanded, Synesius. Let the people discover their freedom, it is time that these traces were thrown off.”

But I can see that Hypatia has noticed the men from the Theological Office, and I have noticed them, and they have noticed us. The air is thick with noticing.

*

“How pleasant, another visit,” — but Machinist Tippit is having none of such niceties.

“You are responsible, and you will stop it,” he rasps. His anger! You can hear his outrage seething behind his mask.

It is a tense moment; he has not come alone.

Whatever his intention, it doesn’t work. The pleading (which is disguised); the threats and blustering (not so disguised). None of it works. He even tries —

“… and they nurse their ignorance, Librarian; they’ve grown to like their sores so much that they scratch them to keep them festering. Words are no use. Only the force and violence of being ruled over absolutely, to the core of their being, makes any sense to them…”

“Free minds, Machinist,” says Hypatia, looking through the window at the perfect circle of the moon, as though that in itself might be enough, and he will understand.

Machinist Tippit says nothing, but my fear is that he does understand, or that if he does not, then his Cardinals will.

*

So. Machinist Tippit’s report to the Cardinals must have been delivered.

There is violence now. The supporters of the Cardinals have appeared, and they swarm like black ants, and there seem to be so many. They burn and strike and attack, and they are aided by Machinists, who pour out of Walkers everywhere.

They are at the gates of the Library, and now they have pushed their way through, and people are wounded and calling for help, but there is none to be had; there is fighting, and there are flames, and now there are dead, and the statues of the gods are falling and crumbling… Serapis, save yourself…

There is fighting everywhere now. She knows what I am thinking.

“Everything flowers, Synesius. All entelechies unfold, according to their natures. Yours. Mine. Theirs. That is all there is.”

The gears in her arms whir as she passes the works of the Philosopher to me. “Get these to safety, Synesius,” her voice clicks.

The noise of the crowd draws closer. She seems to notice that her skin is covered with writing. “And this must go,” she says, and turns towards her rooms.

Buildings burn through the night. The Serapeum’s books and scrolls lie disintegrated in drifts of flame and smoke and ashes. Machinists trample through the fires, heedless of the heat, pouring fuel on the flames.

In just a few hours, a thousand years is dust and ash.

*

The next morning, Walkers beyond counting stream out of the early morning gloom into the towns and villages, through the smoking ruins of the Library and what remains of the Market, coughing clouds of searing gas, loudspeakers blaring:

The air is in danger of dying. Renegades have been burning fires without permission and without the requisite devices in attendance. We are spraying remediant to counter the imminent danger of environmental collapse. Despite the irritation to your lungs, please breathe as deeply as possible. What sort of world do you want to leave for coming generations?

The sky darkens. The sun is hidden behind a mass that suddenly hangs over everything. I have seen engravings of what is above us, so I know what it is. But still, to actually see one…

It is a bolo-airship, so large that its prow and stern seem to disappear into the haze of the distance.

The Cardinals are here.

*

There are many of us, herded into a hall aboard the bolo. I have been taken too, but I am not in chains; I am not being tried before the Council of Cardinals. It is even whispered that if I am careful, I have a future. I am saying nothing.

Hypatia was among the first taken. She stands chained, upright, and she meets their gaze without faltering. I doubt that I have ever loved her as much as I do right now. What follows achieves nothing.

—So you are the wheel, are you? Hypatia says to them, and they do not understand, but I do, because I have seen the butterfly tattooed on the curve of her back.

—I think that the ocean is deep enough, she says later, and again they do not understand, but again I do, and I am not surprised that she says nothing more to them after that, and that there are no tears when they command the Machinists to come and tie her to the rack on which she will now surely die.

There is some sort of ceremony. I don’t know. They pronounce something, observe some sort of outer form, I don’t know.

I realise now that I have been waiting for this moment, anticipating it so much that I feel an awful relief now that it is finally here. From now on, everything that moves, everything that is thought — everything — they all link up, the pieces of everything roar like the wind as they come together, like the cogs in a machine that has no way of stopping.

I can barely hear. There are no individual sounds, there is only one sound, and it is immense, an impenetrable wall that obscures everything.

The inevitability of it shudders in my mind. Is this vengeance, or a lesson for the masses? The hall is crowded.

The names of the things that I see have dissolved; the performance I am watching is beyond names. The Cardinals gather around, and insist that I stand with them. I would look at the floor, but I cannot. The floor has dissolved as well.

Machinists, Tippit among them, with knives and saws and screwdrivers and tools — too small and delicate to determine their names or uses with any certainty — surround Hypatia, and begin to dismantle her.

“I suspected by the look of him that he enjoys killing things,” she says to me, looking up at Tippit as he removes her arms, unscrewing and cutting, cursing, but not impatiently, as her blood soaks into his instruments. She bites her lip, her eyes close for a second, and then open again.

“Does it hurt?” I ask, hopelessly. I can think of nothing else to say.

“The pain is breathtaking,” she replies, as a saw begins to open her chest. “Space and time, they are mere irritants, Synesius,” — but it is harder to understand her now, because her mouth fills with bloody foam as she speaks.

A Machinist begins to remove wire from her chest cavity.

“Aah, the heart…!”, and the Cardinals gather around, “let us see the heart!” and there is glee among them.

“What can I do?” I whisper.

And there is a glance that will cut me in half forever, and then the light in her eyes has gone out.

And I cannot see Hypatia, and I cannot recognise the things and pieces that were her, nor the Machinists, who are still cutting and pulling and excising, nor the Cardinals, who are full of joy and happiness — they are all just parts, and pieces, and their names have all gone.

And as these things fall away, dripping into the dust where her blood gathers — there I can almost recognise what I thought to be me, the thing that gave names to the world, and I see now, quite clearly, that there is nothing there either.

*

The flesh which three times I touched is gone. It has been ground with seashells, and fed to the dogs.

In the end, the Cardinals were full of joy at the death.

They had been surprised when there was no heart to be found inside her. There were organs, true, and blood, true, and cogs and gears and devices of exotic and wonderful manufacture — but there was no heart.

They wondered at this, but only briefly. Then they ordered the flesh disposed of, and the mechanical parts cleaned of blood and gore, and sent to the factories, to be used there, assimilated into the machines that make the Amulets and Feeders and Filters and Conditioners.

“This will make things easier,” said the Cardinals. “Our production values will be greatly enhanced. Going forward, we expect positive impacts on Liquidity and Market Penetration. Stability has returned!”

*

But I know where her heart is; I think I have known all along. Her heart was in the ease and effortless power of her machinery, it was in the heat and pulse of her flesh, and the way the rhythms of them both flowed from the one to the other, and from the other to the one, in the way it all found form in her thinking, and science, and love — there was never any difference between any of them…

And every idea that she had, the urging of every thought towards the freedom of her mind and her spirit — they all left their mark, an imprint of her intent, her joy, in every cog, every gear, every piece of brass and obsidian; they were all her; there was no difference between any of them…

And now, do you see it?

She is everywhere, taken and installed in the machinery of their factories, where the production lines create one thing after another, charm after charm, device after device, again and again without end, every one with Hypatia in them, imago, complete and perfect, imprinted not just in their form but in their essence, in the habits that form them, and from there they go out to the world, delivered by hordes of Walkers to markets and libraries everywhere, where one day — yes, one day, — there will be enough…

*

So, there you have it. There is your answer. That is what happened concerning the pagan Hypatia. Now please, say nothing of this.

* * *

Hi, this is a comment. To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments section in the blog dashboard.vivaldi